Staying Alive: what more of us want to do

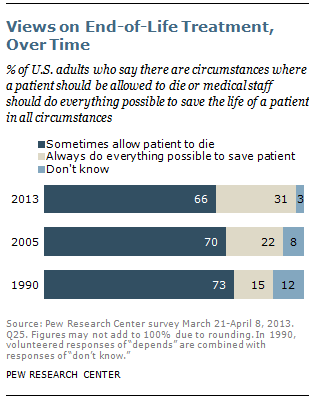

“The share of the public that says doctors and nurses should do everything possible to save a patient’s life has gone up 9 percentage points since 2005 and 16 points since 1990.

From Pew Research Center forum “Views on End of Life Medical Treatment.”

That more adults want everything done to keep them alive at life’s end does not surprise me.

Doing everything vs dying peacefully

But, this may come as a surprise in light of reports saying we want to die peacefully, at home, which assumes fewer interventions. It also seems to fly in the face of numerous initiatives encouraging discussion – with the underlying hope that talking and normalizing the topic will have the effect of reducing the ‘give me everything’ approach.

Where’s the disconnect?

As I continue to talk about life’s end whenever I get the chance, I am constantly confronted with the reality that explains the disconnect: the assumption, presumption and possibly the expectation that we who are not immersed in the world of health specific to end of life will understand the context and repercussions of ‘give me everything’. Even healthcare professionals in areas other then end of life often don’t have a sense of or focus on effects of interventions, beyond the intervention.

On the surface it makes sense: the promise of medical advancements combines with the medical professional’s mandate to heal and cure – often resulting in unrealistic hopes, expectations and goals. Dr Ken Murray‘s How Doctors Die lets us in on the fact that his colleagues adamantly forgo ‘futile treatments’.

Then too, rarely or insufficiently addressed are complications during recovery (eg infection) or complications resulting from the intervention (fixed one thing, broke another) and the very real possibility that – especially in the elderly, frail elderly and terminally ill – that an intervention does not mean life will be restored to previous ‘working order’.

From Dr Jessica Nutik Zitter in the New York Times:

The patient had a severe pneumonia of advanced AIDS. He’d been lying in our intensive care unit for three weeks, a breathing tube thrust into his raw airway, his face a mixture of pain and resignation. His weakened lung tissue had popped in several areas, requiring chest tubes to drain the pockets of pressurized air. He looked like a sea creature with multiple tentacles.

My co-attending doctor in the I.C.U. had tasked me with keeping the patient alive for the weekend. “I’m going to try and get the tubes out on Monday,” he explained. Knowing the prognosis, I asked him if he’d told the family the patient was going to die.

“No. I can keep him alive for now,” he replied. With that, he left.

End of Life is complicated

What doesn’t seem properly explained or discussed are things like bedsores, respiratory infections, compromised immune system, weakened muscles, fatigue, depression and other complications that are likely part of the package of interventions – interventions that seem so well-meaning and logical that – not to purse them is akin to murder, in spite of the huge impact on every other aspect of life.

The big interventions are CPR, feeding tubes, breathing machines, dialysis and some surgeries. For cancer patients, the added wrinkle is best told through black humour: “Why doesn’t an oncologist want the coffin nailed shut: because there’s still one more chemotherapy to try.”

Most adults – we, the public – only know about from these procedures from tv.

Education. Education. Education.

I think all initiatives bringing end of life to the fore are necessary. It’s a tough topic, filled with nuances and emotions and conflicts: there are multiple factors facing those facing end of life. However, without contextualized education, it’s a tall bill to fill.

What I hope is the result of the Pew Report is recognizing the need for beefed up, plain language education. Amongst those needing education are healthcare professionals themselves.

Suggested explorations: Vial of Life (not to be confused with the Fountain of Youth)