Palliative and Therapeutic Harmonization: PATH

In plain language PATH means an assessment and treatment recommendation that takes into account what’s going on with us as a whole person, rather than our specific parts. A worthy goal for all of us, but with particular importance for those both elderly and frail, and who may have a dollop or more of confusion.

Dr Laurie Mallery |

Dr Paige Moorhouse |

Dr. Laurie Mallery, head of the Division of Geriatric Medicine at Dalhousie University and Director of the Centre for Health Care of the Elderly at the QEII Health Sciences Centre in Halifax, Nova Scotia. and Dr Paige Moorhouse with her Masters in Public Health, also practicing at the QEII, are like-minded in their concerns for care of the frail elderly.

Together, these two good doctors took the initiative to research and develop a framework for medical decisions related to the frail elderly. The result is PATH: Palliative and Therapeutic Harmonization. Says Mallery:

“We spent many years, looking at all factors related to the frail elderly.

Drs Mallery and Moorhouse practice and teach at the PATH Clinic . The approach has three parts:

1. Understanding

“The frail elderly are often in and out and in and out of healthcare with many crises, assessed by many people – each of whom brings their own lens. There’s no organizational plan to take this info and use it collectively and understand the significance, for example: is this person near end of life, and should we take that into account in discussing a medical procedure. Sometimes the patient seems frail but they really have a hearing impairment.

2. Clarity of Language

“For those with dementia for example, we must take into account memory loss, behaviour, functionality, response to treatment and life expectancy. The PATH approach helps healthcare providers help patients and families:”

- visualize what that means as relates to medical procedure

- communicate to family

- imagine what that will look like two years down the road

3. Empower

In order to make informed decisions, the patient and family should understand risks, benefits, what life is going to look like, quality of life and quality of death. Dr Mallery contends (and BestEndings proves my agreement):

People don’t have enough information to make an informed decision about end of life treatment. There is often an over-enthusiasm for procedures, even if the patient can’t walk, and is doing poorly to begin with.

Bill Keller, former New York Times editor, writes in an op-ed column: when his wife told her father, “Yes, you’re dying” her father’s response: ‘“so, no more whoop-de-doo.” As Keller says, they could have maintained his failing kidneys by putting him on dialysis. They could have continued pumping insulin to control his diabetes. He wore a pacemaker that kept his heart beating regardless of what else was happening to him, so with aggressive treatment they could — and many hospitals would — have sustained a kind of life for a while.

Mallery and Moorhouse have worked with experts in Diabetes and High Blood Pressure to change medication guidelines for end of life care:

At life’s end, there isn’t the need to tightly control blood sugar or blood pressure. We can reduce the burden of medications.

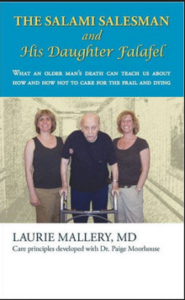

Dr Mallery wrote of her experiences with her dad when he was frail and elderly and suffering from dementia in The Salami Salesman and his daughter Falafal. She shares with me a scenario that’s uncomfortably familiar.

“The doctor asked what my father did for a living. His answer had no bearing on the truth ‘I’m a salami salesmen.’ Yet that’s what when into the chart. This system doesn’t take into account that the frail elderly are often confused.“

The Salami Salesman and his daughter Falafal

My own Monty Python-esque experience: when my mother was was hospitalized whilst living with and dying of a brain tumour that caused unpredictable and sometimes aggressive behaviour. Nurses and docs would storm out of her room ‘I can’t reason with her.’ (well. Duh)